From Lagos to La SAPE: West and Central Africa’s Dandy Legacy, from Colonial Streets to Global Style

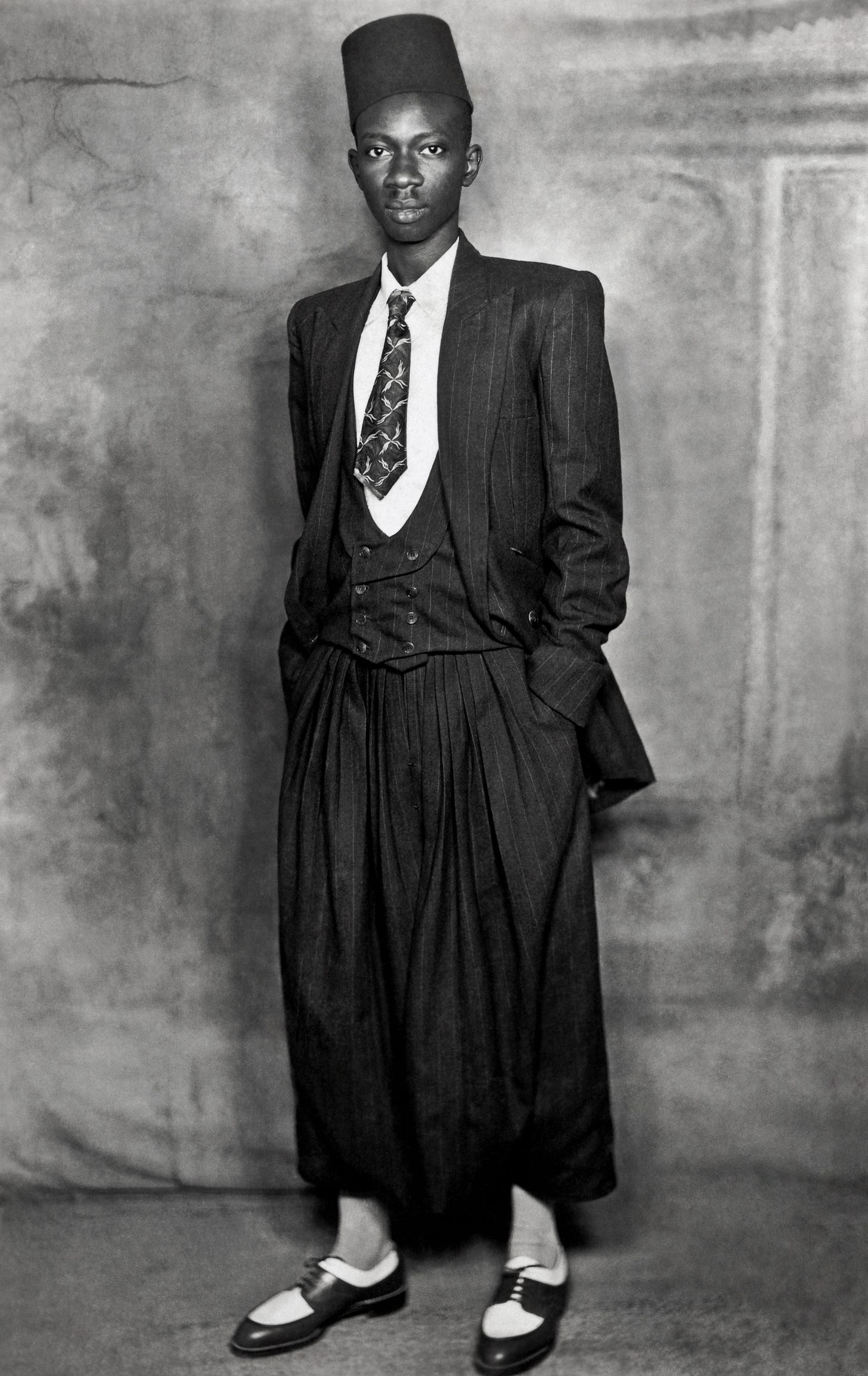

In the damp heat of a West African afternoon, a man once stood in a perfectly cut suit under the equatorial sun. The fabric was all wrong for the climate — wool too heavy, collar too stiff — yet he wore it with a purpose that transcended fashion.

This image could be Lagos in the 1920s or Accra in the 1930s: African men donning three-piece suits and top hats, every seam a subtle act of defiance. As the Met Gala 2025 approaches with the theme “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style,” the echoes of those early dandies grow louder. What began as imposed uniform has evolved into a tailored manifesto, threading ancestral pride through global style.

Today, we journey from the age of colonial rule — when dressing well was a quiet rebellion — to the vibrant present, where West and Central African dandyism stands tall as an emblem of cultural power.

Colonial Dandyism: Oppression and Expression

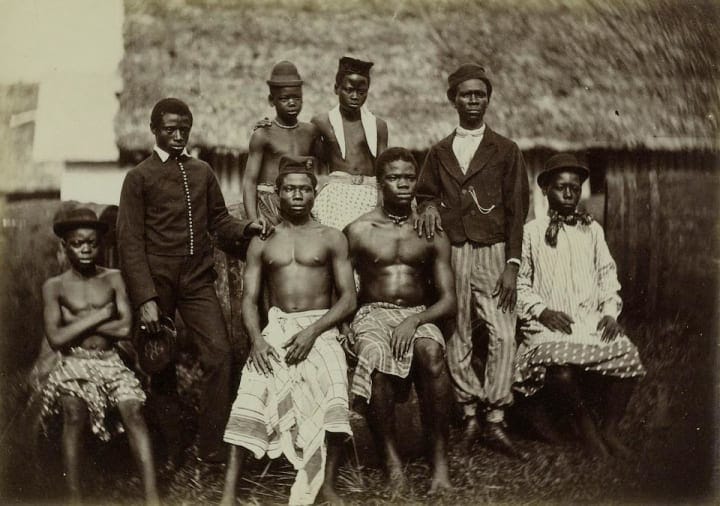

To understand West African dandyism, we begin under the weight of empire. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, European powers brought more than flags and armies, they brought dress codes.

The suit, with its stiff wool and starched collars, became a colonial tool. Missionaries dressed converts in ill-fitting coats; clerks were buttoned into bland blazers —uniforms of submission disguised as civility. In classrooms from Lagos to Kumasi, boys in collars and cuffs were taught that respect came pre-pressed. The European suit wasn’t just clothing; it was a visual mandate to suppress cultural identity and reflect colonial ideals of propriety.

But from the outset, West Africans resisted; not by rejecting the suit, but by rewriting its meaning. In Lagos, a Yoruba merchant might stride off the docks in a charcoal jacket, lapels sharp as defiance. In the Gold Coast (now Ghana), a schoolteacher might pair a pinstriped vest with a kente headwrap, merging British formality with local pride. In Dakar, a man might wear issued trousers but throw a wax-print boubou over his shoulder like a cape, a flash of rebellion against khaki control.

These weren’t just style choices; they were statements. Each fusion of foreign form with native fabric carried a truth louder than words: the cloth may be imposed, but the soul remains sovereign.

A flash of Ankara, a streak of Adire, a boldly mismatched sock, all became coded resistance. Fashion wasn’t just worn, it was wielded. Tailored jackets turned into armor. In Accra and Lagos, these men walked like living manifestos. What once shackled now spotlighted. A crisp seam, a burst of print, a deliberate swagger down colonial streets — all said the same thing: power can be tailored in our image.

Remixing the Rules: West Africa’s Sartorial Awakening

By the mid-20th century, style as resistance had sparked full-fledged subcultures. In Ghana, traveling troupes known as the “Concert Party” used zoot suits — oversized jackets, wide-brimmed hats, two-tone shoes — as tools of satire. Colonial fashion, turned inside out, took the stage as critique.

In Nigeria, young men in Lagos and Ibadan embraced a rising “gentleman style.” Suits were cut from local aso-oke instead of imported wool, and paired with Yoruba fila caps. Dressing well became about embodying modernity, on African terms.

Even traditional attire found new momentum. The flowing agbada evolved into a statement of masculinity and pride, commissioned from elite tailors and layered over shirts and ties, asserting that Nigerian formalwear could rival any tuxedo. In Ghana, once-sacred kente cloth began appearing as trim on Western blazers, or recut entirely into bespoke suits — ancestral stripes draped over colonial silhouettes.

By this point, dandyism was no longer a look, it was a philosophy: dress with such intention that no one can ignore your place in the world. Whether in a Savile Row suit or embroidered robes, West African men had transformed fashion into cultural power.

La SAPE: Congo’s Dandy Revolution

Elegance as Resistance

The spirit of dandy rebellion found one of its boldest expressions in Congo. Out of Kinshasa and Brazzaville emerged La SAPE — La Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes — a movement rooted in reinvention. Under French and Belgian rule, young Congolese men began subverting colonial expectations by turning formal European attire into a tool for autonomy.

French suits became statements. Candy-colored blazers, gleaming shoes, and meticulous posture turned the city street into a stage. By the 1970s, legendary musician Papa Wemba helped catapult La SAPE onto the global stage. His look, Parisian labels, brilliant whites, jewel tones, silk scarves, was pure spectacle. At a time when Mobutu’s government discouraged Western wear in favor of “authentic” African dress, Wemba and his peers pushed back. For them, elegance was liberation.

Fashion, in their hands, became ritual, resistance, rhythm.

From Brazzaville to the World

In the 2000s, the world finally took notice. Photographer Daniele Tamagni’s 2009 book Gentlemen of Bacongo captured the dazzling contrast: Sapeurs in radiant suits, striking proud poses on worn-down streets. Then came Guinness’s 2014 ad Made of More, spotlighting Congolese men who turned neighborhood sidewalks into catwalks…style not as escape, but as assertion. What the world saw wasn’t just flair. It was dignity in motion.

The Legacy Lives On

Today, echoes of La SAPE ripple through global culture. You’ll spot its energy in Burna Boy’s visuals, Solange’s styling, Skepta’s sharp tailoring. It lives on in editorial spreads and red carpet silhouettes. But it’s not just aesthetic, it’s economic and communal. Sapeurs continue to support neighborhood tailors and local fashion economies, finding ways to express dignity through limited means.

To dress well amid hardship is to declare: I am here, I have worth, I will be seen. That’s why the Sapeur legacy endures — a vivid thread in the fabric of Black style history.

Heritage x Modernity: West Africa’s Own Dandy Styles

Tradition Reimagined

Dandyism in West Africa didn’t end with independence, it adapted. As Ghana and Nigeria emerged from colonial rule, men redefined style as a language of pride. European tailoring remained, but it was no longer about assimilation. It was about ownership.

The agbada, once royal formalwear, was reborn in city streets, worn with leather shoes, cufflinks, and embroidered distinction. In Ghana, kente cloth found new life in modern suits, trimmed on lapels or tailored into full blazers. Tradition didn’t disappear, it just evolved.

By the 1980s, style was everyday assertion. In Lagos, sharply cut suits paired with vintage shades and polished loafers. In Accra, fugu tunics and tailored jackets mixed with beads and brogues. African elegance was no longer a nod to Europe. It was an unapologetic flex.

Designers of the Diaspora

This legacy lives on in the hands of designers who treat tailoring as cultural storytelling. Ozwald Boateng’s Savile Row suits lined with African prints, Mai Atafo and Tokyo James blending indigenous textiles with contemporary silhouettes…it’s all part of the same lineage. Even Lagos streetwear has caught the wave: thrifted Italian jackets worn with aso-oke trousers, traditional caps styled with sneakers.

African men today aren’t just dressing to impress. They’re dressing to define themselves.

From Colony to the Met Gala: A Full-Circle Moment

A century ago, the suit arrived in West and Central Africa as a colonial symbol of control. Today, it returns to the spotlight, this time, on our terms.

This year’s Met Gala theme, Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, is a tribute to that transformation. For the first time, the Gala centers Black menswear, and with it, the legacy of Black men who used tailoring as language, identity, and quiet revolt. From Lagos merchants to Congolese Sapeurs, from kente blazers to beaded agbadas, this is not a trend. It’s an inheritance.

So when celebrities ascend the Met steps this year, draped in suiting shaped by culture and intention, they won’t just be showcasing fashion. They’ll be walking in the spirit of men who dressed to be remembered.

Poll Of The Day:

If you’re enjoying our articles, send a matcha our way. 🍵 It’s my favorite drink and now a sweet way to support Fashion Talk—a free platform made with love and intention. To those who already have: your taste is impeccable.

— Amarissa ♡

connect with us: instagram → pinterest → twitter → bluesky